The Legend of Zelda has, in its nearly thirty years of existence, transformed the face of gaming. With its epic sense of adventure, exquisitely designed puzzles, and high fantasy narrative, it has become something of a benchmark for adventure games, inspiring an entire generation of players and game developers to think differently about the medium they love. With the next installment — The Legend of Zelda for Wii U — scheduled to come out later this year, we thought it was the perfect time to re-examine the series history, dividing its rich 30 years of content into different eras.

The Birth of Adventure

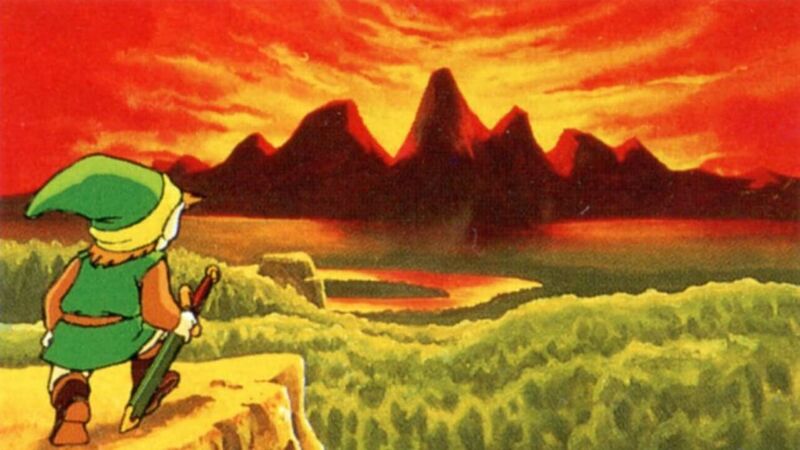

Nintendo released The Legend of Zelda for the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1986. While relatively bare-bones compared to later installments, Link’s first adventure contained nearly all of the series’ major story and gameplay elements: it takes place in Hyrule, Link is tasked with rescuing Princess Zelda from the evil Ganon, and to do so he must collect the eight shards of the Triforce of Wisdom, which he collects by solving puzzles and defeating bosses in the game’s eight dungeons. Nearly every game in the series since has been a variation on this basic recipe.

Shigeru Miyamoto famously said that his inspiration for The Legend of Zelda came from the hillside hikes he used to take as a child. At one point he discovered a cave in the woods, but initially found himself too scared to explore inside. Eventually, he brought along a lantern and summoned up the courage to enter. With The Legend of Zelda, Miyamoto set out to create a “miniature garden” for players to lose themselves in, similar to how he lost himself along the hillside and within the cave. It’s no accident that players start the game by entering a cave to retrieve a sword from the old man.

The game’s first sequel, Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, which is the only game in the series to feature side-scrolling combat and an experience system, is remembered less fondly, though it received glowing reviews upon its 1987 release — less than a year after the release of the first game. The game is notable for its introduction of the magic meter, a mechanic used throughout the series to limit the use of some of Link’s weapons, as well as non-player-characters that are pivotal to the quest. Though there were a few NPCs in The Legend of Zelda, none of them influence the story’s progression in any meaningful way.

Dark Worlds and Shipwrecks

North American Fans of Zelda had to wait five years, until 1992, for The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, a sprawling adventure for Nintendo’s SNES that greatly expanded the scope of the franchise. The series’ focus on narrative set a new standard by incorporating most its gameplay into the story. Its groundbreaking Dark World mechanic, which represented a dangerous mirror-version of the overworld, has been copied by a number of games since.

Two years later, in 1993, Nintendo released The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening for the Game Boy, the first portable Zelda. Surprisingly, this game started out as a handheld port of The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, but evolved into a standalone project under the direction of prolific Nintendo designer Takashi Tezuka. The first game in the series to take place away from Hyrule — in this case, on the mysterious Koholint Island — The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening was just as long and deep as its console counterpart, it’s story just as memorable. In the game, after a shipwreck, Link has to wake the slumbering Wind Fish using eight instruments strewn throughout the Island, obstructed by nightmarish creatures who hope to rule the island themselves.

A New Dimension

After another long five year hiatus, Nintendo returned with a bang: The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, the series’ first foray into the third dimension. A truly epic experience, the game proved the timeless resilience of the series formula. The game was the most cinematic in the series, using cutscenes to tell its engrossing story about the origins of Hyrule and its descent in the wake of the power-hungry Ganondorf. The game pioneered a targeting mechanic for 3D combat, streamlining its sword fights and doing wonders for its camera system. Ocarina of Time also included a time-travel mechanic, a variation on the Dark World from A Link to the Past, allowing Link to use the master sword to travel forward and backwards in time, between the peaceful world prior to Ganondorf’s reign and the hell-scape he ushered in.

Its follow-up, The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask, also centered itself on the concept of time. Much like Groundhog Day, the game made players repeat the same three days over and over again. Dungeons could only be completed within a single three day cycle, and though Link could learn songs that slow the passage the time, this addition nonetheless imbued a sense of urgency missing from previous games in the series. By donning certain masks, link could transform into different species — Deku, Zora, and Goron — to solve puzzles and complete side quests.

The next 3D adventure, The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, came out about a year and a half after the release of Nintendo’s GameCube. Gamers were at first wary about its cel-shaded graphical style — message boards were abuzz with negativity following the release of a teaser trailer unveiling its cartoonish look — but those aesthetic misgivings were abruptly washed away upon release. The first Zelda game with an aquatic overworld, The Wind Waker was a dream for armchair navigators, allowing players to sail around a flooded Hyrule — called The Great Sea — on a talking ship named King of Red Lions, discovering new islands and pilfering treasure from the sea’s bottom. While some found its seafaring tedious, the game is universally adored for its animation, combat system, and dungeon design.

A Hero’s Waggle

Nintendo proved they were listening to fans by announcing that their followup to The Wind Waker would feature an art style in line with the dark and gritty nature of their N64 games. After a development cycle plagued with delays, Nintendo announced they would be releasing two versions of their next Zelda game, The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess: one for the GameCube, and one as a launch title for the Wii. The GameCube version played similarly to previous games in the series, using a simple targeting system for its combat segments. The Wii version, however, was the first game in the series to use motion controls. Players would swing the Wiimote and waggle the Nunchuck during combat, making the game’s sword-fighting all the more engaging. Taking place in a Hyrule torn apart by the encroaching twilight realm, Twilight Princess allows link to transform into a wolf during certain parts of the game.

Fans had to wait until 2011 for the next game in the series. The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword expanded on the motion controls of its predecessor by requiring players to use the Wii Remote Plus, an improved version of the peripheral with greatly improved accuracy. Players could now enjoy a one-to-one sword fighting experience, directing the angle of their slices to ensure timely defeat. The game’s overworld exists in the skies above Hyrule, and players must mount a large bird called a Loftwing to travel between destinations. It’s art style was something of a hybrid of Wind Waker and Twilight Princess, supposedly inspired by impressionism, featuring a semi-cel-shaded take on the more-realistic art direction of the latter.

Adventure in the Palm of your Hand

All the while, Nintendo kept releasing portable installments in the Zelda saga. Oracle of Ages and Oracle of Seasons for the GameBoy color represented a successful creative collaboration between Nintendo and Capcom. The games, released simultaneously, were standalone adventures made all the more interesting by linking them together. On the Game Boy Advance, The Legend of Zelda: The Minish Cap allowed players to explore Hyrule’s nooks and crannies by shrinking down to microscopic size with the help of a talking hat named Ezlo.

With the DS, Nintendo released a pair of successful installments, each with their own interesting twist on the Zelda formula. The Legend of Zelda: Phantom Hourglass introduced a single large dungeon central to the game’s progression, the likes of which could only be tackled in small stretches after receiving the Phantom Hourglass, which makes Link invulnerable to the dungeon’s curse. Its follow-up, The Legend of Zelda: Spirit Tracks, imagines Link as the conductor of a train — his primary means of transport across the game’s overworld.

Most recently, Nintendo released a followup to The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past with The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds. Featuring the same overworld as its predecessor, A Link Between Worlds also incorporates a Dark World mechanic, allowing Link to travel between Hyrule and Lorule (I see what you did there, Nintendo!) to solve puzzles and gather items. For the first time in the series, players would have to rent or buy many of the game’s items, adding new weight to the collection of rupees. The game also allows Link to merge into walls as a simplistic painting, allowing him to reach new areas on a 2D plane.

What’s Next?

The much-anticipated The Legend of Zelda for Wii U is scheduled to release this year, with recent reports indicating that the game is “nearly finished.” That said, Nintendo is also releasing the NX, which means there’s a chance the game will launch for both systems, similar to how Twilight Princess came out for both GameCube and Wii. The game looks beautiful and enormous: a demo from about a year ago showcased the game’s lush and sprawling landscapes, with Link riding Epona and using a small parachute to catapult himself across the terrain. We can’t wait to try it for ourselves — thankfully there are whispers that the game might be at this year’s E3.

Until then, we’ll be re-watching the trailer over and over again.