I want to tell you about my favorite personal interest and ruling passion as a scholar, the thing I find it hard to live without. Television animation. Specifically, animation produced for television consumption. This is hard to do for a couple of reasons. First, it has tended, historically and now, to be blamed for many things that it is hardly the root cause of. Violence that occurs in it, for example, was equated with real-life violence for a number of years, although now those who obsess over real-life violence have now largely moved over to blaming others based on actual evidence but second-hand hearsay. Therefore, it was uncalled for and unfair. Then again, most television animation characters are perfectly capable of tearing those who act in such a fashion apart verbally and physically fairly easily in their own universes, so things are even, I suppose.

Secondly, it’s hard to try to write serious scholarship about something that’s overwhelmingly about humor. We human beings seem to have a bit of a funny relationship with humor. We all enjoy laughing, but at different things. One person’s belly laugh is another person’s head-scratcher. And the least enjoyable thing about jokes is trying to explain them to people who don’t understand.

Then there is the same sort of ambivalent passive-aggressive relations we have with television and animation on their own. It’s never been entirely fashionable to say that you enjoy watching the “boob tube”, or that you are an adult who enjoys an entertainment medium that was supposedly made for children only. In the first case, mass communication has often been the target of elitist snobs who want to control culture, and television is a prime example of their disdain because it was probably the most mass form of communication before the Internet. And because children are denied the right to vote and other forms of citizenship, the things they want and understand are often decided in absentia for them, without their input. Which explains a few things about the media that is directed squarely at them, at least sometimes.

What I am trying to say by these examples is that television animation is often judged on a prejudicial basis, with people assuming they know what it is about, based on second or third-hand knowledge or receding childhood memories, in a way that prevents a meaningful analysis of both historical and contemporary trends from occurring. Which I find distasteful.

My position on television animation is different from others chiefly because I am a fan who has followed and continues to follow the genre avidly and I am an author who has written scholarship about the field and will likely continue to do so in the future. In both roles, I am convinced you can only know what is going on about these programs by watching them closely and examining the historical literature related to them. You have to be able to sit down through whole episodes to get an understanding of what they’re all about.

And while it isn’t always an easy job, it can be a rewarding one as well.

For starters, if you actually involve yourself in the stories instead of trying to keep track of acts of violence or other presumed violations of your sense of taste, they can be pretty interesting things.

Clever tales of heroes and villains locked in mortal combat, friendships and family bonds broken and remade over and over again, extremely ticklish allusions and references to real life and media events and things, made in the most unlikely and unexpected of ways. Totally likable and enjoyable creatures, the kind of people you would want to have as brothers, sisters, friends or lovers, regardless of whether they be humans, animals or other supernatural creatures. And no judgments cast based on race, gender, class etc.- unless you happen to be an evil villain, in which case you’re on your own, buddy.

The kicker is that most of these events are conducted in ways that defy realism rather than accept it, and reinforce the belief that the world would be a better place if these things were real. Animals talk. Children are wise and profound beings, and adults incredibly stupid and short-sighted. All things related to the supernatural and science fiction are frequently accepted as fact rather than denied. And the more of these things that can be played for as many laughs as possible, the better. The worlds created by the animators seem cleaner and fresher than ours in any number of ways, physical and moral. That’s probably one of the main reasons why I keep coming back- there are people and ways of thinking that we don’t have here that we could most certainly use.

If only real life problems could be dealt with that easily, or real life people that easy to understand. As someone challenged with Asperger’s syndrome, I frequently find truth harder to deal with than fiction- which is why I’m glad that fiction of this kind exists.

But some people still try to doubt the value or treat it in a schizophrenic way. The Academy of Television Arts and Sciences has been giving worthy animated shows Emmys for years, but you’d never know it watching the telecast these days. The animated Emmys are stuck in the hell of the technical (pardon me, Creative Arts) ceremony right now, so a lot of viewers would never even know they exist. Out of sight, out of mind. So how would they even know about them?

That’s just the tip of the iceberg, though. It goes a lot deeper than that.

Back in the 1950s, people actually thought television was like a drug, that nobody could possibly free itself from the desire to constantly watch, regardless of what was on. And what was the supposed entry point for children into this addiction? You guessed it. Cartoons (a label that now sounds something like a racist slur to me) got the blame. Granted, there wasn’t a lot of original television animation to begin with in those days, but the label stuck.

But this was also the period when the nascent Hanna-Barbera studio was at its peak, with the antics of Huckleberry Hound, Yogi Bear, and, later, the Flintstones. And let’s not forget Jay Ward and his brilliant crew responsible for Rocky and Bullwinkle, which, over time, has become probably the most influential series of its kind, within the genre and the wider world as well.

Still, few were willing to give it much credit for what it accomplished.

In the ‘60s and ‘70s, it got worse. A lot of people who didn’t know a damn thing about what they were talking about accused television animation of being too violent”This was ridiculous considering how it actually was at the time- there were numerous live-action gun-toters then blasting away in prime time while animation only intended to be funny and exciting without consequence. Yet animation, because it was falsely assumed to be appreciated by children and children only, got blamed. It was forced to go through the artistic equivalent of chemical castration by draconian censorship at the hands of the misnamed Standards and Practices department, which turned much of the animation under their watch into a parody of itself simply because it could. No cable or Internet in those days, so if you wanted to produce animation for television then, you had to play by the network’s rules. And, if they wanted it bland and unthreatening, then, by God, you made it so.

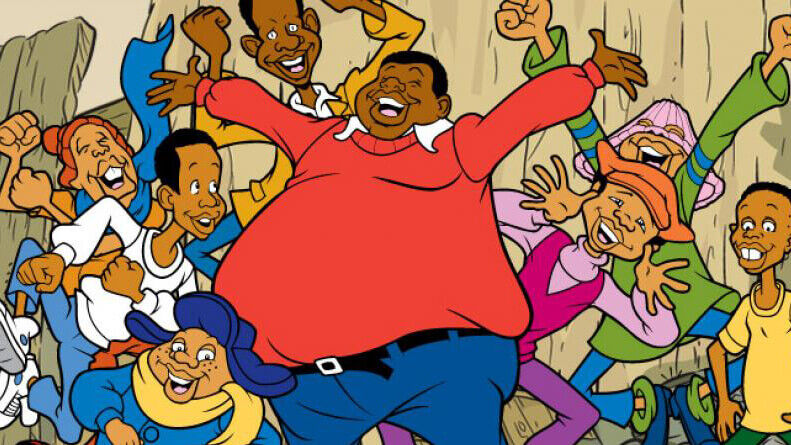

Not that nothing of value came out of that time. Lou Scheimer’s Filmation produced much of its greatest work during this time, including its collaboration with Bill Cosby, Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids, which brought new demographics and new storytelling strategies to television animation that continue to reverberate. If ever there was an underrated company doing a yeoman job in this field, it was Filmation.

In the ‘80s, television animation got flack for being part of the rampant consumerism of the time. Somehow, it was thought that basing a show around toys, video games or greeting card characters was too “commercial” for a genre that had been reduced more to edification than entertainment. It is true that some of the shows of the time were like that, but, again, cutting all the chaff away reveals some rather nice wheat hiding there in the shadows.

Again, Filmation thrived, reaping considerable rewards for going off boldly into the new realm of syndication to escape network tyranny, creating the boldly original action-adventure hits He-Man and She-Ra. Alas, the studio fell victim to another kind of tyranny- international corporate politics- when its parent company abruptly closed it down without notice, and it never produced another series.

Finally, in the ‘90s, television animation began fighting back.

The Simpsons came along and fired the first warning shot, and then nothing was the same again.

Nobody expected much of it, it being originally a filler piece on a variety show on a shoestring network with an uncertain identity. But it transcended everyone’s expectations and became not only a hit prime time program but a major cultural force. It was highly unusual then for a mere animated program to do this, and almost immediately the role and function of animation in television began to change, largely for the better. Opportunities came about and were seized with great success.

The major shift came when the networks slowly began to abandon television animation and other children’s programming, mainly due to declining financial profits and ceded the field to the cable giants which now largely run the television animation industry- Nickelodeon, Cartoon Network, and Disney.

It had been accepted in live-action television since the 1970s that it was both creatively and financially feasible to allow skilled writers, producers,and directors to produce programming without corporate interference. Beginning in the mid-1990s with Cartoon Network, and spreading to the others as well, this mode of production now became the dominant one, with the result being the felicitous mode of production which has produced innumerable classics, too many to be fully discussed here. Finally, after quite a long struggle, people in the television animation were able to produce the kind of shows they wanted to make, what they felt was much more worthy of the attention of the audience than anything that preceded it. It not only expected that kind of attention- it demanded it. And, given how people loved what they made then and still do now, it truly was worthy of that attention.

Of course, now, television is not what it used to be. Instead of trying to unite us, it has become part of the problem, breaking us all up into separate audience components. How can television animation, or any TV genre worth its salt nowadays, try to compete with the blizzard of online offerings stealing away the people who used to be loyal towards it?

I, for one, think it will endure. For this reason….

If the diverse group of characters in television animation has anything single thing in common, it is their ability to fight back, physically and/or verbally, against any sort of threat confronting them, for they know this is the only way to overcome any sort of evil in their path. Their creators and their cable television landlords are no less formidable in similar circumstances. And outside media competition would just be another obstacle to most of them.

If you understand this, you will know why, while most of the mainstream TV is now battered and bloodied, television animation is still standing.