At the 69th Annual Academy Awards, Independence Day was nominated for Best Visual Effects. It faced steep competition that year — Dragonheart featured a full CG dragon, and the Academy nominated Twister for its exceptionally realistic portrayal of the effects of wind on Bill Paxton’s hair. But the Academy did the right thing, and Independence Day won the Oscar. Here’s why it deserved it.

The first 15 minutes alone are loaded with incredible effects. The main titles whoosh in and explode apart, letting you know this flick is gonna singe your eyebrows, man. Then we find ourselves on the moon. There’s a deep bass rumble, and the lunar dust vibrates as the alien mothership passes overhead. It’s a great little moment that establishes tone and scale. Sure, it’s scientifically preposterous, but who cares? The beautiful thing about this sequence is that wasn’t rendered in a computer. The moonscape was a handmade miniature. The Apollo 11 plaque in the foreground was real prop photographed on a soundstage somewhere. The mothership was a miniature, too, but it had to 12 feet long to achieve the necessary level of detail.

A few minutes later, the film takes us back to Earth’s orbit. We’re tracking a satellite as it crosses paths with the mothership. The mothership intrudes into the frame, and just when we think the satellite is going to smash into it, the satellite keeps going, growing ever smaller, until it is a speck against the massive ship. Only then does the speck explode in an adorable little fireball. By the way, nothing explodes without a fireball in Independence Day. This is a film about a world in which everything is full of fire just waiting to be let out.

Then, we’re introduced to the Destroyers (the monument-zapping saucers), which may be the film’s most impressive miniatures. Another beautiful shot in the movie’s first act shows the Destroyers separating from the mothership and falling to Earth like huge flower petals. The Destroyer miniature was about 12 feet wide and lit from the inside by a dense network of fiber optics. Every shot of the Destroyer ships is a triumph of effects work. The compositing never sucks, the scale is always believable, and the detail on the ships is fascinating.

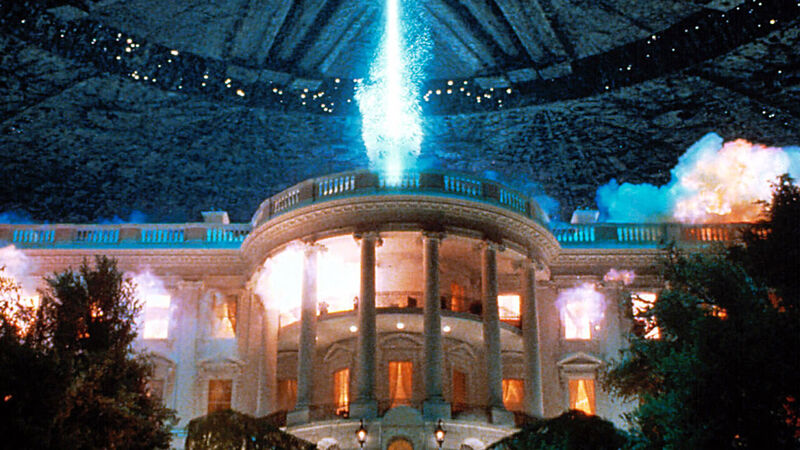

After a whole lot of setup and character introductions (they don’t get to Will Smith until 20 minutes in), the Destroyers fall into place above the cities of Earth. The montage in which buildings and monuments are covered by the destroyers’ creeping shadows is such pure, classic iconography. That shot of the shadow moving up the Washington monument is a standout in Roland Emmerich’s career as a visual storyteller. I just wish he’d made a film after Independence Day that surpassed its effortless display of indelible blockbuster imagery. It may not be smart (even the strip club has an American flag hanging on stage), but there is power in the simplicity and execution of the images in this film.

Then, 45 minutes into the film, the destruction begins. And it’s awesome. Tiny building after tiny building is blown to smithereens in spectacular fashion. Keep in mind that effects crews can’t just stick explosives on any old miniature and hit the bang switch. The Empire State Building as seen in Independence Day is a 14-foot miniature, designed specifically to explode in a certain way. I didn’t count how many miniature buildings were seen exploding in Independence Day, but every one was specifically built to give you that signature “shattering” effect when the shockwave hits. It’s a gleefully pornographic repurposing of a particular type of Americana: atomic bomb test footage.

Destruction of major cities and monuments has become such a regular occurrence in contemporary cinema that we’ve become numb to it. Too often, it all looks the same. And none of it is as indelible as this:

The film’s dogfights, while not quite as rich in iconic imagery as the first act and the destruction sequences, recall the dogfights of the original Star Wars trilogy. They’re not as balletic as the original Death Star assault, but Captain Hiller (Will Smith) does get a short trench run sequence as he’s chased by the alien fighter. Both Hillard and the alien crash in the desert, and Hillard manages to knock an alien out with a single punch and drag it most of the way to Area 51, where Dr. Okun (a perfectly cast Brent Spiner) can get a good look at it.

The film’s aliens aren’t all that cool. They’re small, with saucer-shaped heads and large, mirror-finish eyes. But the biomechanical armor they walk around in is a great design by Patrick Tatopoulos (The Underworld series). A great goopy surgery sequence, in which Dr. Okun attempts to extract the alien from its armor, is my favorite scene in the film. It’s classic creature horror right out of The Thing, with a disgusting practical monster and a great jump scare.

It may be a dunderheaded and cheesy affair, but Roland Emmerich’s Independence Day was (and still is) an incredible effects showcase. Aside from some relatively minimal digital assistance, the effects seen in the film aren’t terribly different from something like James Cameron’s Aliens: miniatures, practical creatures, matte paintings, and optical know-how. So while Independence Day was not a revolution in effects filmmaking, it may be the epitome of effects filmmaking before the CGI revolution.