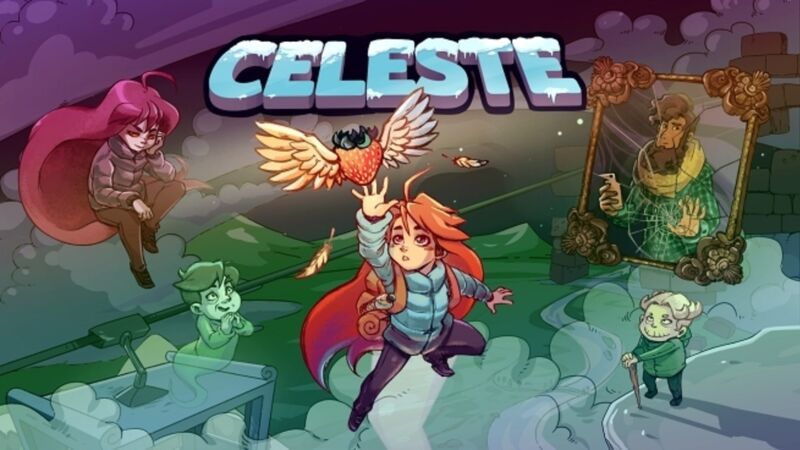

Celeste is a game about climbing a mountain. That’s the elevator pitch, anyway. I wasn’t really sure what to expect as I booted it up for the first time and found myself at the base of this titular mountain. I had heard rumblings that there was more to it than that, but it still took me by surprise when it was revealed that, among other things, Celeste is a game about dealing with anxiety.

I’ve been living with the dirty ‘A’ word for the past two years now. Some days I’m fine, other days I’m not. Describing its pervasive feelings, and those of its sinister bedfellow – the panic attack – is a difficult proposition, beyond listing the easily identifiable physical symptoms.

I’ve no doubt used these before when detailing the range of feelings you might barrel through when playing a horror game like Alien: Isolation. Sweaty palms, shortness of breath, numbness in the extremities, a racing heartbeat — you get the jist. Only now they occur when there’s not even a single xenomorph in sight.

At Death’s Door?

In hindsight, the first time anxiety crept up on me was more terrifying than the reality of the situation would warrant. It was the second time that forced me to take action. What should have been a peaceful walk with my dog turned into a life-altering moment. When my breathing became erratic and my heart started racing, I immediately jumped to the macabre conclusion that I was having a heart attack.

Being in the middle of a field, with help so far away, I figured this would be the end of me; killed by a dodgy heart on a fateful dog walk. The mass hysteria and rapid boom-boom-boom of my heart soon subsided after what felt like an eternity, but that uneasy feeling never quite went away. After a glacial walk home, feeling like I was at death’s door, I booked a doctor’s appointment for the following morning.

For the next few weeks I ran the full gamut of heart tests. My doctor monitored both my heartbeat and blood pressure; I took an electrocardiogram test, and gave blood at the local hospital. The results came back, and physically, there was nothing wrong with me: it was all in my head.

Peace in Pixels

What I mistook for a heart attack was actually a panic attack, and I was soon diagnosed with a generalised anxiety disorder. I have no idea what triggered it or why, but medication has at least eased the apprehensive feelings I would experience for no discernible reason on a near-daily basis. Instead, my anxiety will manifest in nonsensical situations, because I’m home alone, engaging with public transport, or sitting in the darkened room of a cinema, to name but a few.

Video games have been a useful form of escapism when the war inside my head is at its most histrionic. Whether I let my mind wander the opulent streets of Kamurocho in Yakuza Zero, or cooperate with friends to pop headshots and score screamers in the likes of Destiny 2 and FIFA 18‘s Pro Clubs. Yet none of these games have had a profound effect on the way I grapple with my anxiety like Celeste has.

Although I’ve never played Towerfall before, I was attracted to developer Matt Makes Games’ latest because of comparisons to the magnificently irreverent Super Meat Boy. I knew there was more to it than comparable gameplay hooks, but without wanting to spoil myself, I jumped in blind.

Patiently Punishing

Like Team Meat’s audacious console debut, Celeste is a devilishly difficult 2D platformer. It demands pinpoint precision and a mastery of its various systems to progress through its myriad stages, but unlike Super Meat Boy‘s brazenly bloody adventure, it takes no glee in punishing the player.

Make no bones about it, you will die a lot during this treacherous ascent beyond the jagged peaks of Celeste Mountain. There is a death counter after all — you’ll start to feel like the video game equivalent of a red shirt in Star Trek. Yet meeting your demise never feels like the gut-punch it so often does in other masocore platformers of Celeste‘s ilk.

“Be proud of your death count!” one loading screen tooltips says. “The more you die, the more you’re learning. Keep going!” This is a game that wants you to succeed and takes wholesome joy in encouraging you to surpass its trickiest challenges. Celeste is like a soft, comfy hug of a game — all the while killing you for the 400th time in three hours — and this warmhearted nature comes across in its narrative, too.

Apprehensive protagonist Madeline is not a professional mountain climber. She’s on a self-imposed mission to scale Celeste’s peak for very personal reasons. Suffice to say, Madeline suffers from anxiety, depression, and panic attacks, and much of the storytelling is focused on how the mountain forces her to confront these issues.

You see, Celeste is not a normal mountain. There’s something mysterious and otherworldly about it, and Madeline is warned from the outset that it has a habit of showing people who they really are.

Art Imitating Life

The ramifications of Madeline’s visit are felt early on when a menacing part of her psyche breaks free. Part of Me, as it’s known, is a physical manifestation of Madeline’s anxiety and mental anguish. She’s an antagonist and tormentor; the part of Madeline’s brain that makes her doubt herself, and tells her she isn’t good enough. The relationship between the two is at the crux of Celeste‘s story, but I want to focus on one powerful scene in particular.

At the end of chapter four, Madeline meets up with Theo, a fellow adventurer she had previously encountered near the base of the mountain. Theo is the complete opposite of Madeline; he’s self-assured, cool, calm, collected, a jokester, and a proponent of good selfies — though there’s more depth to him below the surface.

After he takes a comically long tumble directly onto his face, the two of them board a rickety-looking gondola in order to traverse to the other side of a perilous chasm. After a short conversation between the two budding friends, Part of Me disrupts the peace by stopping the gondola dead in its tracks, leaving Madeline and Theo dangling hundreds of feet in the air with no obvious escape.

Understandably, this terrifying situation causes Madeline to have a panic attack, which is artfully represented by ominous tendrils that blot out the sun and gnaw away at her from every angle.

Madeline’s personality still shines through here as she snaps at Theo about what a stupid idea this was, but in this moment he’s the perfect companion for what she’s going through.

Soothing A Worried Mind

As Madeline shrinks into herself, Theo recounts a trick he learnt from his granddad. “Picture a feather floating in front of you,” he calmly instructs as an orange hued feather appears in the centre of the screen. “Your breathing keeps that feather floating. Just breathe slow and steady, in and out.” It’s a simple exercise, but when your mind is racing this simplicity is essential.

Gradually the screen fades to black and you’re left with nothing but this feather, gently flowing up and down. You have to adjust Madeline’s breathing to keep the feather in its graceful flutter. Maintain a peaceful rhythm for long enough and you’re brought back to reality: the tendrils have dispersed, Part of Me is gone, and the gondola is mercifully moving again.

Thanks to Theo, his granddad, and Madeline’s deft handling of the situation, her panic attack has passed by without incident. All the two of them are left with is a memorable selfie to commemorate the occasion — snapped at the exact moment the gondola came to a petrifying halt.

At the time, this scene resonated with me because I was witnessing a video game protagonist struggling with an all-too-familiar sensation. Madeline might have a traditional arsenal of death-defying platforming abilities, but she’s relatable — she feels very human.

Cartoony Catharsis

When I could sense myself succumbing to panic’s pernicious clutches just a few days ago, I closed my eyes and all I could do was picture Madeline and that feather. I slowly inhaled, then exhaled, syncing each breath with the feather, recalling Theo’s words, and taking inspiration from Madeline’s strength. Instead of overreacting, I was able to focus and think rationally, and the panic attack gradually faded away without ever escalating to unbearable heights.

As Madeline edges closer and closer to Celeste’s peak, Matt Makes Games introduces a spine-tingling gauntlet that forces you to utilise every skill you’ve learnt throughout Madeline’s exhausting journey. Reaching the top of the mountain after all of this is elating, yet it was that moment further down, on that stranded gondola, that will stay with me forever.

Taking what Theo said and applying it to alleviate a very real struggle is the biggest accomplishment I can take from Celeste.

I know visualisation is a technique often used in meditation to help relax and control one’s breathing, but in this case Celeste‘s depiction is heightened by its context, and speaks to the tangible impact of video game storytelling and interaction. Anxiety might always be with me, but there are ways to ease its suffocating grip. I just didn’t expect to find one halfway up a digital mountain, but I’m glad I did.