One of the elements of the animated series Adventure Time‘s storytelling that has endeared it to so many fans across disparate age groups, and frustrated many trying to get into it, was its initial lack of an overriding metanarrative. It chose instead to focus on wacky hijinks and “random” humour. But as the show’s lore and character development has expanded beyond its original core concept, adding depth and facets to it along the way, parallels begin to emerge.

The first line of the Tao Te Ching, the principal text of Taoist philosophy, is often loosely translated thus: “The tao that can be described is not the true tao.” This fundamentally frames the discussion of Taoist philosophy as one of myriad interpretations, facets of a larger whole that no single person can fully comprehend. It thus reflects the mysterious and inscrutable nature of the universe itself. Ironically, the fact that no single interpretation of the Tao, or “way”, is canonized as true makes each interpretation of it equally valid, and its tenets more universal.

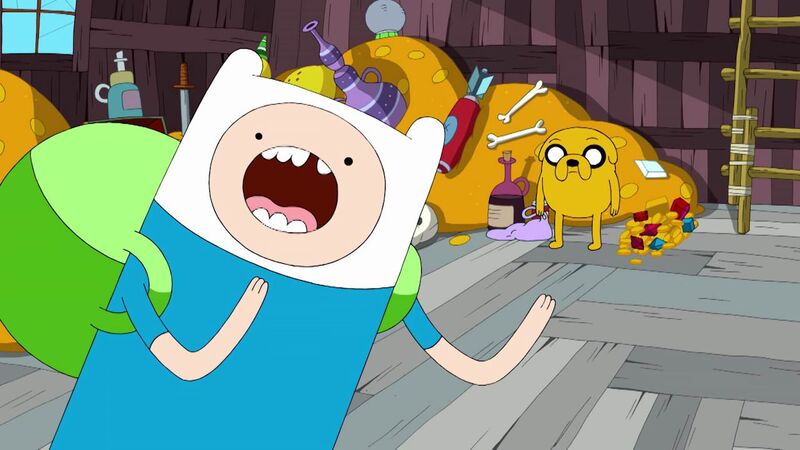

This is not the first time that Taoist principles have inspired or been applied critically to works of art or fiction. In this case, we’re looking at its relationship to Adventure Time, specifically its protagonist, Finn the Human. He’s a plucky and adventurous hero who fights monsters and evil with his adopted brother Jake the Dog.

“Now, in all of these Oriental societies – Indian, Chinese or Japanese – art is not simply the art of the canvas or the brush or sculpture; it’s the art of life. […] This awareness of existence is the main thing, and all of the crafts, all of the actions of life, are opportunities to experience this divine presence which is our life. The function of the artist is to render that in a particularly acute way for the senses.”

– Joseph Campbell, “Wu Wei: Doing By Not Doing”, I.3.5 Creativity in Oriental Mythology

Vinegar, Life As It Is and the Nature of Heroism

Like many religions, Taoism uses allegory to explain its principles, most notably in the art subject known as The Vinegar Tasters. It depicts three figures standing at a vat of vinegar and dipping their fingers in to taste it. Their reactions are emblematic of their philosophical viewpoints. The first, Confucius, grimaces at the sour taste, representing his belief in humanity’s need for rules and order. The second, Buddha, finds the taste bitter. This represents the belief in transcending the pain and suffering of life to achieve Nirvana. But the third, Lao Tsu, smiles ecstatically. From the Taoist perspective, sourness and bitterness come from the interfering and unappreciative mind. Life itself, when understood and utilized for what it is, is sweet.

In his video essay on The Legend of Zelda, Arin Hanson argues that, “as a player, your idea of fun ends up making you a hero… Why aren’t all these other [NPCs] going out and fighting monsters and questing? Cause they’re not heroes! They don’t find it fun! But you, the player, find it fun. You find killing monsters fun. You find ridding the world of evil things fun. That makes you a hero.”

These notions rhyme with Finn’s own perspective of why he lives as he does. He fights monsters, gets into adventures with his friends and encounters bizarre mythic creatures. This is what gives him the most joy in life. Doing otherwise would be counter to his own nature. It doesn’t come from a tragic backstory or a heroic destiny. (It does, sort of, but we’ll get to that.) The only logical answer presented for it is that Jake’s idea of being an older sibling was to “give him something sharp and get him to fight bad guys.”

Wu Wei, the Uncarved Block and Going With The Flow

This brings us to another principle of Taoism, wu wei, or “the action of non-action”. As stated above, Lao Tsu believed that trying to apply rigid dogma and logic to life simply problematized the act of living it. The character of Princess Bubblegum reflects this principle. She’s a well-meaning ruler and scientist whose obsession with logic and reason often blinds her to her faults. This thinking often creates problems rather than solutions and alienates her from her friends and subjects.

Finn’s lack of book-smarts compared with PB is never shown as something to be frowned upon. By simply acting in accordance with his instincts and true nature, Finn will often reach solutions others cannot. His (occasionally unorthodox) way of dealing with trauma and difficulty is to simply move on from it. He goes with the flow and trusts that the universe will put him where he needs to be. This state of being, referred to as “the uncarved block”, represents Lao Tsu’s ideal for living: the concept of living unburdened by (but not ignorant of) knowledge and experience. This prevents one’s thinking and actions being limited or fixed.

This culminates during his time trapped in the Hall of Egress. No amount of strategy or force allows Finn to escape the confines of the dungeon. It is only when he blindfolds himself, sheds his clothes and identity and trusts his instincts to guide him that he is able to escape.

Yin-Yang, Catalyst Comets and Duality

Finn’s backstory doesn’t feature many of the hallmarks of the archetypal hero’s journey. It doesn’t follow Joseph Campbell’s monomyth theory or contemporary variants popularized by Hollywood. However, his status as a hero does have some links to the larger metanarrative of the show itself. Many episodes allude to Finn having lived several past lives prior to his current one, with his original incarnation being a comet that fell to earth.

This becomes a major arc in the show’s sixth season. The approach of the Catalyst Comet is imminent. It’s an interstellar object that crashes into Ooo – itself a post-apocalyptic version of Earth – once every millennium. It brings with it an agent of change, reincarnating a thousand years later. When the eldritch entity Orgalorg attempts to consume the Comet, only to be thwarted by Finn, the entity within the Comet explains to Finn that he was once one of the Comet’s previous avatars, as was The Lich, a death-bringing malevolent force that led to both the decimation of Earth and the creation of Ooo as we know it from magical/nuclear fallout.

This duality reflects that of the yin-yang. The yin-yang is a prominent symbol in Chinese philosophy that is used to describe how seemingly opposite or contrary forces may actually be complementary, interconnected, and interdependent in the natural world. It also describes how they may give rise to each other as they interrelate to one another. The Comet entity itself resembles the yin-yang in shape. In Taoist metaphysics, distinctions between good and bad, along with other dichotomous moral judgments, are perceptual. They’re not real. The duality of yin and yang – Finn and the Lich, good and evil, fire and ice, all exist as part of an indivisible whole.